The “gold” in Golden West Sign Arts is literal: thin leaves of gold applied with a brush. In Derek McDonald’s kit you’ll find: a guilder’s mop, guilder’s tip, pieces of abalone, and the gold leaves themselves, in a book layered between folds of tissue paper.

“It’s so thin it will blow away if you breathe on it,” says Tina Vines, Derek’s partner in the obsession with the hand-painted and hand-crafted.

The other gold is spooned out of Dixie cups onto pieces of wood and cardboard with an ordinary brush: plain materials transformed into something unique in the world.

“It’s very simple,” Derek says. “As a sign painter, you memorize three basic letter styles. Everything is based off that. I think younger designers who get into it may be missing that, because there’s no one around to teach them.”

There are few places left to learn. Most of the old sign-painting trade schools have shut their doors. Like letterpress and other traditional methods of printing, the craft of sign-painting is a highly skilled blue collar profession, with a long history, that technology has recently marginalized.

McDonald is serious about keeping this tradition alive. Not in a dogmatic way, but with a contagious enthusiasm for the best of what old and vanishing techniques and crafts can teach us about hand-painted lettering and design.

And he’s ambivalent at best about it becoming turned into yet another fine arts trend.

“It’s more of a craft than an art,” Derek says. “That’s what I always tell people.”

He says he’ll take on any job, and charge a rate as competitive as he can with digital signprinters. He’s painted on trucks, boats, pieces of industrial machinery. He gave the neighboring hair salon a deal on a hand-painted sign. Most of his clients are small and local businesses.

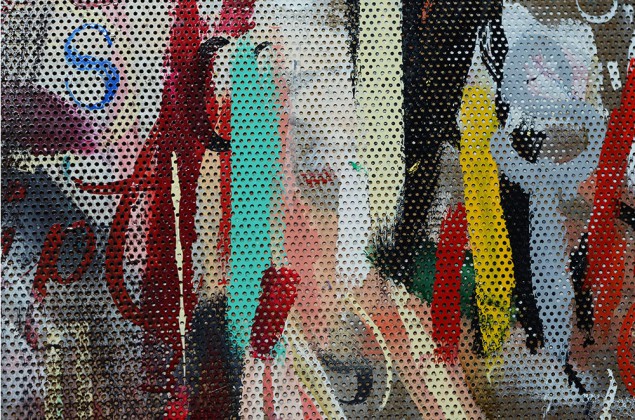

In other words, Derek is less interested in getting his work up on gallery walls than on city streets. He has that in common with graffiti artists, muralists, and other creators of public art.

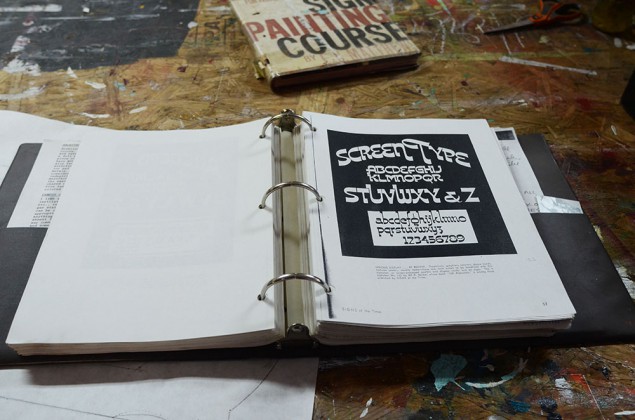

In their studio on San Pablo Avenue in West Berkeley, the shuffling, dusty sounds of Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys play in the background. Tina pulls out old books on the sign-painting craft, and Derek pours coffee for visitors. They live in a room behind the studio and spend most of their waking hours here, with Herbie, their dog. They’re a kind, welcoming pair, the sort of couple you’d want to invite to your weekend barbeque.

McDonald is open about his art-making process and wants to share it with people. It’s hard not to admire that, because it’s such a rarity in regards to art-making, where there is so much hyped-up mystery and deliberate vagueness. While I was there taking notes and asking questions, Aurora snapping pictures, another visitor showed up; a young graphic design student who just wanted to observe and learn.

There were three basic styles learned traditionally, McDonald explains, that were the foundation of the sign painter’s art. First was “Gothic,” also known as “Egyptian stroke”—a basic block letter.

Then, there’s “thick and thin” with a combination of heavier and lighter strokes, and lastly, there’s “script,” or flowing cursive with connected letterforms.

A sign-painter would also have a basic “casual” style, which is the all-caps, slightly slanted lettering frequently seen on hand-painted signs.

Derek goes on to illuminate other tricks of the trade.

A sign will often start with a ‘paper pattern’—either a thumbnail sketch or a full-size outline. Another technique is ‘line scribing’—marking off straight lines with a triangle to create a frame, or grid, for the letters.

To transfer from paper, there’s a fascinating bit of old technology: perforating the paper with a ‘pounce wheel’ or even an ‘electro-pounce’ (cutting edge circa half a century ago).

Set the paper over the final surface, and apply chalk dust—and there the sign painter has a temporary pattern to guide their hand that they were able to sketch first with a pencil on a drafting table, as carefully as they needed to.

When asked what he thinks about the current revival in popularity of hand-made typography, Derek responds that it’s a good thing, but with a few caveats.

These days, he’s likely to get requests like “‘can you do this conference call with my designer in Brooklyn?’ . . . there’s the expectation, sometimes, that if it’s hand-lettered it’s going to be super-elaborate, super-ornate.”

In contrast, “There was a simplicity about old signs,” he says, and describes a Tiburon restaurant with a hand-painted sign that read… Restaurant.

There’s ample evidence around the studio that McDonald can do ornate, fancy lettering quite well. But I also note that in the handmade marketing ephemera of a bygone time that plasters the walls, there’s a lot of clean, no-nonsense sans-serif lettering.

Tina Vines points out a paradox of today’s hand-crafted lettering: in the past, sign-painters would strive to make custom lettering appear perfect, as if it had been machine-made.

Now, it’s just the opposite. The visual idiosyncracies, even imperfections, show “a human hand made it.” And, as such, are desirable.

Derek McDonald grew up in the Los Angeles and Reno areas before moving to the East Bay at age 17, and he’s been here since then; he’s now 30. In addition to sign-painting, he plays drums for a Western Swing band, the West Coast Ramblers. While we watch, he paints a decal on his new drum kit.

McDonald was first inspired by the hand-painted signs he saw in the Bay Area, many by San Francisco native Jimmy the Saint. From there, he dove into his own research, collecting manuals from the early 20th century such as “The Sign Painting Course” by E.C. Matthews.

Derek keeps opening the door to his studio to tattoo artists, graphic design students, and others who are interested. He’s not only doing his part to keep sign-painting alive, he’s helping spread the knowledge of an endangered craft, one that makes the visual environment in towns and cities a little more human and warm, a little less mechanized and cold.

“You can see in some towns,” Tina says of their travels to places like the Midwest, “where a certain sign-painter worked for years. They’ve sort of put their signature on that town.”

Without his name anywhere in sight, Derek McDonald’s signature is popping up all over California.

Find Golden West Sign Arts here.

Fascinating article – thank you. I am in awe of the skill here and sad that it is disappearing. Good on them for keeping the art alive.