“Only an act of true love can thaw a frozen heart.” This is the take-away from the latest Disney animated blockbuster, Frozen. As the final denouement approaches, it remains unclear what this act of love will be, or indeed whose heart needs unfreezing: is it Elsa’s, the elder sister whose uncontrollable power to create snow and ice has unleashed a global calamity, or is it Anna’s, her younger sister, whose heart was accidentally impaled by a jet of ice in an attempt to convince Elsa to undo the effects of her curse?

In the final scene, the two women find themselves on the frozen bay: Anna at death’s door, about to be consumed by ice spreading from within, and Elsa, still the ice princess but broken-spirited at what she has done to the environment and her sister, about to be executed by Hans, the evil prince. Anna looks one way, and sees the man who truly loves her, dashing to her rescue: a kiss from him might be the act of love that will save her; she looks the other way and sees her elder sister in mortal danger. Instead of attending to her own rescue, Anna raises her arm to shield her sister from Hans’s sword and in that instant becomes a block of ice, frozen solid. As it falls, the sword shatters against her outstretched arm. Elsa, devastated, finally breaks down into tears, embracing her sister. As her own heart thaws, so too does that of her sister; the curse is broken. Summer returns.

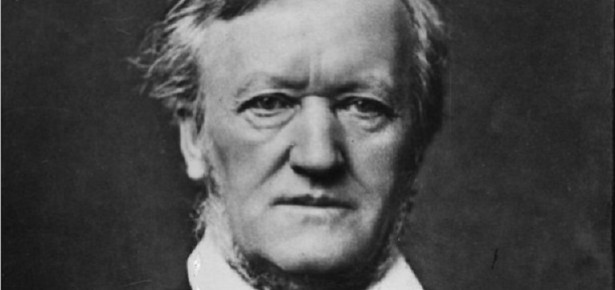

Before Disney, it was Wagner and only Wagner who created moments of such cataclysmic intensity, deeply personal but with universal reach. Frozen is about love, and even more about family. Two sisters, orphaned when their parents perish at sea, who only have each other. No less in Wagner, where all his greatest heroes are without parents, cast adrift, alone in the world: Siegfried, Tristan, Parsifal. Even more, Frozen is about self-sacrifice, especially the woman who sacrifices herself, a motif constantly recurring in Wagner’s operas: Senta in the Flying Dutchman, Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, Brünnhilde in Götterdämmerung, and in virtually every other work by Wagner. It is a powerful image and one which, from the perspective of gender equality, is troublingly patriarchal: why always the woman? And usually a woman sacrificing herself for a man? At least in Frozen, the woman sacrifices herself for another woman: her sister. But isn’t there also something fundamental here? I wonder if, in our wish to streamline and equalize the sexes, we have come to overlook the unique power of the maternal drive, unavoidably one of self-sacrifice and often on a scale that is both epic and quotidian. What’s more, you don’t have to be a mother to be maternal.

Finally, what is it that fuels the core of Frozen and makes it such compelling drama? Surely the soundtrack, which is constructed around a series of musical-verbal motifs which are woven into the fabric of the film, connecting the present to the past and giving hope for the future. This is Wagner through and through, and nowhere more than in his 17-hour epic The Ring of the Nibelungs which is held together by a series of simple musical ideas mind-blowingly varied and amended, each time gathering meaning, as the drama winds it way through time. Don’t be put off by the length, or by the occasional loud singing, or by the mythical time and place: yes, the Ring is about global cataclysm and epic struggle but, at its heart, it is even more about family, about despair, about hope, and about the power of love.

Latest Comments

Have your say!